What Does The Word Crackle Glass On Your Lungs Mean

Basis-glass opacity (GGO) is a finding seen on chest x-ray (radiograph) or computed tomography (CT) imaging of the lungs. Information technology is typically defined as an area of hazy opacification (x-ray) or increased attenuation (CT) due to air displacement by fluid, airway plummet, fibrosis, or a neoplastic procedure.[one] When a substance other than air fills an surface area of the lung it increases that surface area'south density. On both x-ray and CT, this appears more than grey or hazy every bit opposed to the normally dark-appearing lungs. Although information technology can sometimes be seen in normal lungs, common pathologic causes include infections, interstitial lung disease, and pulmonary edema.[2] [iii]

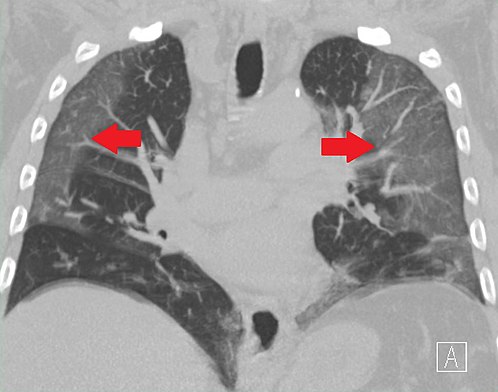

Loftier-resolution CT epitome showing ground-drinking glass opacities in the periphery of both lungs in a patient with COVID-19 (red arrows). The side by side normal lung tissue with lower attenuation appears every bit darker areas.

Definition [edit]

In both CT and chest radiographs, normal lungs appear dark due to the relative lower density of air compared to the surrounding tissues. When air is replaced past some other substance (due east.m fluid or fibrosis), the density of the area increases, causing the tissue to appear lighter or more greyness.[4]

Footing-glass opacity is most often used to draw findings in high-resolution CT imaging of the thorax, although it is also used when describing chest radiographs. In CT, the term refers to one or multiple areas of increased attenuation (density) without concealment of the pulmonary vasculature. This appears more grey, as opposed to the normally dark-appearing (air-filled) lung on CT imaging. In breast radiographs, the term refers to one or multiple areas in which the usually darker-actualization (air-filled) lung appears more than opaque, hazy, or cloudy. Ground-glass opacity is in contrast to consolidation, in which the pulmonary vascular markings are obscured.[3] [5] GGO can be used to describe both focal and lengthened areas of increased density.[5] Subtypes of GGOs include diffuse, nodular, centrilobular, mosaic, crazy paving, halo sign, and reversed halo sign.[6]

Causes [edit]

The differential diagnosis for ground-drinking glass opacities is broad. Full general etiologies include infections, interstitial lung diseases, pulmonary edema, pulmonary hemorrhage, and neoplasm. A correlation of imaging with a patient'southward clinical features is useful in narrowing the diagnosis.[7] [8] GGOs can be seen in normal lungs. Upon expiration at that place is less air in the lungs, leading to a relative increase in density of the tissue, and thus increased attenuation on CT. Furthermore, when a patient lays supine for a CT scan, the posterior lungs are in a dependent position, causing partial collapse of the posterior alveoli. This leads to an increment in density of the tissue, resulting increased attenuation and a possible footing-drinking glass appearance on CT.[iii]

Infectious causes [edit]

In the setting of pneumonia, the presence of GGO (equally opposed to consolidation) is a useful diagnostic clue. Nearly bacterial infections atomic number 82 to lobar consolidation, while atypical pneumonias may cause GGOs. Information technology is important to note that while many of the pulmonary infections listed below may lead to GGOs, this does non occur in every case.[2] [6] [viii] [9] [10]

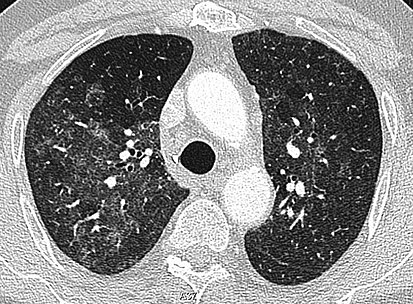

High-Resolution CT image in a patient with Pneumocystis pneumonia infection showing footing-glass opacities.

Bacterial [edit]

- Diffuse

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae

- Chlamydophila pneumoniae

- Legionella pneumophilia

- Focal or nodular

- Mycobacterium

- Nocardia

- Septic emboli

Viral [edit]

- Adenovirus

- Coronavirus (including MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2)

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

- Canker Simplex Virus (HSV)

- Human being metapneumovirus (HMPV)

- Influenza

CT image showing ground-drinking glass opacification in the posterior of the right lung (screen left).

- Measles

- Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV)

- Varicella zoster

Fungal [edit]

- Pneumocystis jirovecii (PCP)

- Invasive aspergillosis

- Candidiasis

- Mucormycosis

- Pulmonary cryptococcus

- Paracoccidioidomycosis

Parasitic [edit]

- Pulmonary Schistosomiasis

Non-infectious causes [edit]

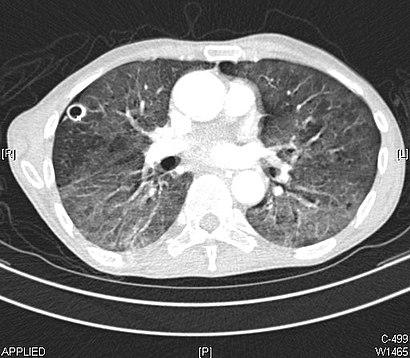

CT image showing patchy areas of ground-drinking glass opacities representing pulmonary edema.

Exposures [edit]

- Aspiration pneumonitis

- Drug toxicity (most common include cyclophosphamide, amiodarone, carmustine, methotrexate, and bleomycin)

- Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

- EVALI

- Radiations pneumonitis

Idiopathic interstitial pneumonia [edit]

- Acute interstitial pneumonitis

- Desquamative interstitial pneumonia

- Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia

- Non-specific interstitial pneumonia

- Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia

Neoplastic processes [edit]

- Lung adenocarcinoma

CT paradigm showing lengthened GGOs throughout both lungs. An abscess is besides noted in the correct lung (screen left).

- Adenocarcinoma in situ of the lung

- Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia

Additional causes [edit]

- Acute eosinophilic pneumonia

- Cholesterol granulomas

- Focal interstitial fibrosis

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Lymphatoid granulomatosis

- Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis

- Pulmonary calcifications

- Pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis

- Pulmonary contusion

- Pulmonary edema

- Pulmonary hemorrhage

- Pulmonary infarction

- Sarcoidosis

- Thoracic endometriosis

Patterns [edit]

At that place are 7 general patterns of ground-glass opacities.[6] When combined with a patient'southward clinical signs and symptoms, the GGO pattern seen on imaging is useful in narrowing the differential diagnosis. Information technology is of import to notation that while some affliction processes present as but 1 pattern, many tin can present with a mixture of GGO patterns.[6]

Diffuse [edit]

The diffuse design typically refers to GGOs in multiple lobes of 1 or both lungs. Broadly, a diffuse pattern of GGO can be caused by displacement of air with fluid, inflammatory debris, or fibrosis. Cardiogenic pulmonary edema and ARDS are common causes of a fluid-filled lung. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage is a rarer crusade of diffuse GGO seen in some types of vasculitis, autoimmune conditions, and bleeding disorders.[6]

Inflammation and fibrosis tin also cause diffuse GGOs. Pneumocystis pneumonia, an infection typically seen in immunocompromised (e.g. patients with AIDS) or immunosuppressed individuals, is a classic cause of diffuse GGOs. Many viral pneumonias and idiopathic interstitial pneumonias tin can also lead to a lengthened GGO pattern. Radiations pneumonitis, a side effect of pulmonary radiations therapy, can lead to pulmonary fibrosis and diffuse GGOs.[6]

Nodular [edit]

There are numerous potential causes of nodular GGOs which can be broadly separated into benign and malignant conditions. Benign conditions potentially leading to the formation of nodular GGOs include aspergillosis, acute eosinophilic pneumonia, focal interstitial fibrosis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, IgA vasculitis, organizing pneumonia, pulmonary contusion, pulmonary cryptococcus, and thoracic endometriosis. Focal interstitial fibrosis presents a unique claiming when differentiating from malignant nodular GGOs on CT imaging. It is typically persistent over long-term imaging follow-upward and shares a like appearance to malignant nodular GGOs.[10]

Pre-cancerous or malignant causes of nodular GGOs include adenocarcinoma, adenocarcinoma in situ, and atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH). One large review report plant that 80% of nodular GGOs which were nowadays on repeated CT imaging represented either pre-cancerous or malignant growths. Differentiating between pre-malignancy and malignancy on the basis of CT alone can pose a challenge to radiologists; notwithstanding, there are several features that that are indicative of pre-malignant nodules. AAH is a pre-malignant cause of nodular GGO and is more than ordinarily associated with lower attenuation on CT and smaller nodule size (<ten mm) compared to adenocarcinoma.[11] In addition, AAH often lacks the solid features and spiculated appearance that are often associated with malignant growths.[ten] In dissimilarity, as adenocarcinoma becomes invasive it volition more ofttimes cause retraction of adjacent pleura and may show an increase in vascular markings. Nodules >fifteen mm well-nigh always represent an invasive adenocarcinoma.[ten] [eleven]

Centrilobular [edit]

Centrilobular GGOs refer to opacities occurring inside 1 or multiple secondary lobules of the lung, which consist of a respiratory bronchiole, small pulmonary avenue, and the surrounding tissue.[iii] A defining feature of these GGOs is the lack of involvement of the interlobular septum. Potential causes of centrilobular GGOs include pulmonary calcifications from metastatic affliction, some types of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, aspiration pneumonitis, cholesterol granulomas, and pulmonary capillary hemangiomastosis.[six]

Mosaic [edit]

A mosaic pattern of GGO refers to multiple irregular areas of both increased attenuation and decreased attenuation on CT. Information technology is often the result of occlusion of small pulmonary arteries or obstacle of modest airways leading to air trapping.[6] Sarcoidosis is an additional cause of a mosaic GGOs due to the formation of granulomas in interstitial areas. This may coexist with granulomatosis with polyangiitis, leading to diffuse areas of increased attenuation with ground-glass appearance.[6]

Crazy paving [edit]

The crazy paving pattern may occur when at that place is both interlobular and intralobular widening. This sometimes resembles a road paved with irregular bricks or tiles. It is typically diffuse, involving larger areas of one or multiple lobes. At that place are a variety of potential causes, including Pneumocystis pneumonia, late-stage adenocarcinoma, pulmonary edema, some types of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, sarcoidosis, and pulmonary alveolar proteinosis.[six] COVID-19 has also been shown to occasionally cause GGOs with a crazy paving pattern.[12]

Halo sign [edit]

A halo sign refers to a GGO that fills the area around a consolidation or nodule. This is a most unremarkably seen in various types of pulmonary infections, including CMV pneumonia, tuberculosis, nocardia infection, some fungal pneumonias, and septic emboli. Schistosomiasis, a parasitic infection, too commonly presents with the halo sign. Important not-infectious causes include granulomatosis with polyangiitis, metastatic illness with pulmonary hemorrhage, and some types of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias.[half dozen]

Reversed halo sign [edit]

A reversed halo sign is a central ground-glass opacity surrounded by denser consolidation. According to published criteria, the consolidation should form more than iii-fourths of a circle and be at least 2 mm thick.[13] It is frequently suggestive of organizing pneumonia,[14] simply is only seen in about 20% of individuals with this status.[thirteen] It can also be present in lung infarction where the halo consists of hemorrhage,[fifteen] as well equally in infectious diseases such as paracoccidioidomycosis, tuberculosis, and aspergillosis, too as in granulomatosis with polyangiitis, lymphomatoid granulomatosis, and sarcoidosis.[16]

-

CT showing diffuse ground-glass opacities in periphery of both lungs in patient with COVID-xix.

-

CT image showing ground-glass nodule (circled).

-

CT image showing centrilobular design of GGOs in patient with pulmonary tuberculosis. Note the minor, nodular areas of increased attenuation in both lungs.

-

CT paradigm showing mosaic attenuation pattern in patient with hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Notation the alternating, patchy areas of increased and decreased attenuation, particularly in the left lung (screen correct).

-

CT paradigm showing crazy paving pattern of ground-glass opacities in both lungs.

-

CT image showing halo sign in patient with pulmonary aspergillosis. Note ground-drinking glass opacification surrounding the area of consolidation (circled).

-

CT image of reversed halo sign in patient with organizing pneumonia.

COVID-19 [edit]

CT paradigm in patient with COVID-19 showing bilateral ground-glass opacities at the periphery of both lungs.

Ground-glass opacity is among the most common imaging findings in patients with confirmed COVID-19.[17] [18] 1 systematic review establish that among patients with COVID-19 and aberrant lung findings on CT, greater than 80% had GGOs, with greater than 50% having mixed GGOs and consolidation.[17] GGOs with mixed consolidation has most often been establish in elderly populations.[19] Several studies have described a blueprint among initial, intermediate, and hospital discharge imaging findings in the disease course of COVID-xix. Virtually commonly, initial CT imaging reveals bilateral GGOs at the periphery of the lungs. During initial stages, this is well-nigh often found in the lower lobes, although involvement of the upper lobes and right eye lobe has likewise been reported early in the disease course.[17] [nineteen] This is in contrast to the two similar coronaviruses, SARS and MERS, which more commonly involve only i lung on initial imaging.[20] [21] As the COVID-19 infection progresses, GGOs typically become more diffuse and often progress to consolidation.[12] [19] This is sometimes accompanied by the development of a crazy paving pattern and interlobular septal thickening.[19] In many cases the near astringent pulmonary CT abnormalities occurred within 2 weeks after symptoms began.[18] At this signal, many individuals begin showing resolution of consolidation and GGOs as symptoms meliorate. However, some patients take worsening symptoms and imaging findings, with farther increment in septal thickening, GGOs, and consolidation. These patients may develop lung "white-out" with progression to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) requiring treatment escalation.[18] [22]

Preliminary reports accept shown many patients have residual GGOs at time of discharge from the hospital. Due to the novelty of COVID-19, large studies investigating the long-term pulmonary CT changes have yet to be completed. However, long-term pulmonary changes have been seen in patients subsequently recovery from SARS and MERS, suggesting the possibility of similar long-term complications in patients who have recovered from acute COVID-nineteen infection.[23]

History [edit]

The first usage of "ground-drinking glass opacity" past a major radiological order occurred in a 1984 publication of the American Journal of Roentgenology. It was published as role of a glossary of recommended nomenclature from the Fleischner Society, a group of thoracic imaging radiologists.[24] The original published definition read equally: "Any extended, finely granular blueprint of pulmonary opacity within which normal anatomic details are partly obscured; from a fancied resemblance to etched or abraded glass."[24] Information technology was again included in an updated glossary by the Fleischner Society in 2008 with a more than detailed definition.[25]

Run into also [edit]

- Pulmonary consolidation

- Pulmonary infiltrate

References [edit]

- ^ Goodman LR (2015). Felson's principles of chest roentgenology (Fifth ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. pp. Supplement 3, e36–e80. ISBN978-0-323-77795-7. OCLC 1134689400.

- ^ a b Mettler Jr FA (2019). Essentials of radiology (Fourth ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. pp. 299–331. ISBN978-0-323-56787-9. OCLC 1053711279.

- ^ a b c d Sharma A, Abbott 1000 (2019). Thoracic imaging (Third ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. ISBN978-0-323-59699-2. OCLC 1022265855.

- ^ Herring Westward (2020). Learning radiology : recognizing the basics (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. two–4. ISBN978-0-323-56728-2. OCLC 1096282271.

- ^ a b Walker CM, Chung JH (2019). Müller's imaging of the chest (2d ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. pp. 109–137. ISBN978-0-323-53179-five. OCLC 1051135278.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j 1000 El-Sherief AH, Gilman MD, Healey TT, Tambouret RH, Shepard JA, Abbott GF, Wu CC (2014). "Clear vision through the haze: a practical approach to ground-drinking glass opacity". Electric current Problems in Diagnostic Radiology. 43 (3): 140–58. doi:x.1067/j.cpradiol.2014.01.004. PMID 24791617.

- ^ El-Sherief AH, Gilman MD, Healey TT, Tambouret RH, Shepard JA, Abbott GF, Wu CC (2014). "Articulate vision through the brume: a practical arroyo to ground-drinking glass opacity". Current Bug in Diagnostic Radiology. 43 (3): 140–58. doi:ten.1067/j.cpradiol.2014.01.004. PMID 24791617.

- ^ a b Parekh Yard, Donuru A, Balasubramanya R, Kapur Due south (July 2020). "Review of the Chest CT Differential Diagnosis of Footing-Glass Opacities in the COVID Era". Radiology. 297 (three): E289–E302. doi:10.1148/radiol.2020202504. PMC7350036. PMID 32633678.

- ^ Rossi SE, Erasmus JJ, McAdams HP, Sporn TA, Goodman PC (one September 2000). "Pulmonary drug toxicity: radiologic and pathologic manifestations". Radiographics. 20 (5): 1245–59. doi:ten.1148/radiographics.20.five.g00se081245. PMID 10992015.

- ^ a b c d Park CM, Goo JM, Lee HJ, Lee CH, Chun EJ, Im JG (one March 2007). "Nodular ground-glass opacity at sparse-section CT: histologic correlation and evaluation of alter at follow-up". Radiographics. 27 (ii): 391–408. doi:10.1148/rg.272065061. PMID 17374860.

- ^ a b Lee HY, Choi YL, Lee KS, Han J, Zo JI, Shim YM, Moon JW (March 2014). "Pure ground-glass opacity neoplastic lung nodules: histopathology, imaging, and management". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 202 (3): W224-33. doi:10.2214/AJR.13.11819. PMID 24555618.

- ^ a b Ye Z, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Huang Z, Vocal B (August 2020). "Chest CT manifestations of new coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-nineteen): a pictorial review". European Radiology. xxx (8): 4381–4389. doi:10.1007/s00330-020-06801-0. PMC7088323. PMID 32193638.

- ^ a b Foley R, et al. "Reversed halo sign (lungs)". Radiopaedia . Retrieved 2 Jan 2018.

- ^ Elicker BM, Webb WR (2012). Fundamentals of Loftier-Resolution Lung CT: Mutual Findings, Mutual Patterns, Common Diseases, and Differential Diagnosis. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN9781469824796.

- ^ Wu G, Schmit B, Arteaga 5, Palacio D (2017). "Medical image of the week: pulmonary infarction- the "reverse halo sign"". Southwest Journal of Pulmonary and Disquisitional Care. xv (4): 162–163. doi:x.13175/swjpcc124-17. ISSN 2160-6773.

- ^ Karthikeyan D (2013). High Resolution Computed Tomography of the Lungs: A Practical Guide. JP Medical Ltd. p. 256. ISBN9789350904084.

- ^ a b c Bao C, Liu X, Zhang H, Li Y, Liu J (June 2020). "Coronavirus Illness 2019 (COVID-19) CT Findings: A Systematic Review and Meta-assay". Periodical of the American College of Radiology. 17 (vi): 701–709. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2020.03.006. PMC7151282. PMID 32283052.

- ^ a b c Salehi S, Abedi A, Balakrishnan S, Gholamrezanezhad A (July 2020). "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Systematic Review of Imaging Findings in 919 Patients". AJR. American Periodical of Roentgenology. 215 (one): 87–93. doi:10.2214/AJR.20.23034. PMID 32174129.

- ^ a b c d Salehi South, Abedi A, Balakrishnan South, Gholamrezanezhad A (July 2020). "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Systematic Review of Imaging Findings in 919 Patients". AJR. American Periodical of Roentgenology. 215 (i): 87–93. doi:10.2214/AJR.xx.23034. PMID 32174129.

- ^ Ooi GC, Daqing M (Nov 2003). "SARS: radiological features". Respirology. eight Suppl (s1): S15-9. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00519.x. PMC7169195. PMID 15018128.

- ^

- ^ Carotti M, Salaffi F, Sarzi-Puttini P, Agostini A, Borgheresi A, Minorati D, et al. (July 2020). "Chest CT features of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia: primal points for radiologists". La Radiologia Medica. 125 (7): 636–646. doi:x.1007/s11547-020-01237-4. PMC7270744. PMID 32500509.

- ^ George PM, Barratt SL, Condliffe R, Desai SR, Devaraj A, Forrest I, et al. (November 2020). "Respiratory follow-up of patients with COVID-nineteen pneumonia". Thorax. 75 (11): 1009–1016. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215314. PMC7447111. PMID 32839287.

- ^ a b Tuddenham WJ (September 1984). "Glossary of terms for thoracic radiology: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee of the Fleischner Society". AJR. American Periodical of Roentgenology. 143 (iii): 509–17. doi:10.2214/ajr.143.3.509. PMID 6380245.

- ^ Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Müller NL, Remy J (March 2008). "Fleischner Club: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging". Radiology. 246 (three): 697–722. doi:ten.1148/radiol.2462070712. PMID 18195376.

External links [edit]

- Footing-Glass Opacity of the Lung Parenchyma: A Guide to Analysis with High-Resolution CT

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ground-glass_opacity

Posted by: mageesudeings.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Does The Word Crackle Glass On Your Lungs Mean"

Post a Comment